Journal of Applied Biosciences 212: 22462 – 22485

ISSN 1997-5902

Pathogenicity and effects of Soil Physicochemical Properties on Fungal Disease Incidence and Severity of Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz.) in Bamenda, Cameroon.

Azinue Clementine Lem*1, Mbong Grace Annih2 and Tonjock Rosemary Kinge1

1Department of Plant Sciences, Faculty of Science, The University of Bamenda, P.O. Box 39, Bamenda, North West Region, Cameroon.

2Department of Plant Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Dschang, P.O. Box 96 Dschang, Cameroon

Email of Corresponding Author: azinuelem6@gmail.com

Submitted 06/08/2025, Published online on 30/09/2025 in the https://www.m.elewa.org/journals/journal-of-applied-biosciences https://doi.org/10.35759/JABs.212.5

ABSTRACT

Objective: Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz.) is considered as one of the primary food crops in Cameroon. Its cultivation is challenged by numerous pests and diseases, yet proper identification of the pathogenic agents is still ongoing. Fungal pathogens of cassava have been previously under looked, since researchers dwell more on viral pathogens. This research aims to evaluate the pathogenicity and effects of soil physicochemical properties on fungal disease incidence and severity of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz.) in Bamenda, Cameroon.

Methodology and results: In Nkwen and Bambili, 20 cassava farms were evaluated for disease incidence and severity and soil characteristics. A greenhouse study involved inoculating 16-week-old cassava plants with five common fungal isolates using stem injection at 10⁴ conidia/ml. Fusarium oxysporum caused the highest disease incidence (80%) and severity. Bambili recorded higher disease levels (66%, severity score 4) compared to Nkwen (50%, score 3). While soil physical properties were similar across sites, chemical properties (pH water, pH KCl, OC, OM, N%, P(mg/kg), C/N, Ca (Meg/100g, Mg (meg/100), K(meg/100g), Na and (meg/100g) varied. A strong positive correlation existed between pH KCl and disease severity (P=0.05), and between disease incidence and severity (P=0.001). All tested fungi were pathogenic, though some showed milder symptoms.

Conclusion and application of findings: This study confirmed that, all five fungal isolates, were pathogenic to cassava particularly Fusarium oxysporum. Disease incidence and severity were higher in Bambili than in Nkwen, likely influenced by variations in environmental and soil chemical conditions, especially pH KCl, which showed a significant correlation with disease severity. The soil Physical properties remained same across sites, but chemical properties varied and had an impact on disease intensity. Results from this study indicates how important pathogenicity and soil properties are in the management of cassava diseases. Monitoring soil pH can serve as an early indicator of disease risk. Developing and promoting resistant cassava varieties can control fungal diseases. The study also highlights the need for soil management and farmer education programs to reduce cassava losses and support sustainable production, especially in regions with similar soil conditions.

Key words: Disease Incidence, Disease severity, Fungi, Pathogenicity, Soil Physicochemical Properties

INTRODUCTION

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Cranz.), a member of the Euphorbiaceae family, is among the most significant food crops globally (Nyaka et al., 2015). It is widely used, particularly in the food, pharmaceutical, and textile industries. Both the roots and leaves are edible, with the roots being a vital source of calories in tropical regions, as well as in parts of Asia and Latin America (Nyaka et al., 2005). Despite its relatively low protein-to-carbohydrate ratio compared to other staple crops (Sayre, 2011), cassava remains a crucial dietary component for nearly a billion people around the world (Prochnik et al., 2012). In areas such as Africa and Brazil, the leaves are also consumed by humans and used as animal feed, contributing additional protein to the diet (Hillocks, 2002). Culturally, cassava is valued for its versatility in traditional dishes, often prepared by methods like boiling, roasting, and fermenting (Meyo and Dapeng, 2012; Hillocks, 2002). In the pharmaceutical industry, cassava roots are processed into starch and fermented to produce ethanol (Adelekan, 2010), while the leaves have demonstrated strong antioxidant properties (Boukhers et al., 2022). Bioactive compounds such as carotenoids and phenolics in cassava help neutralize free radicals, thereby lowering oxidative stress and reducing the risk of chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease and certain cancers (Boukhers et al., 2022). Moreover, cassava leaf extracts have been found to inhibit the formation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, suggesting potential benefits for managing inflammatory diseases (Boukhers et al., 2022). In textiles, cassava provides raw materials for the production of gums and alcohol (Nyerhovwo et al., 2021). By 2005, cassava ranked fifth globally in food crop production after maize, rice, wheat, and potatoes (Nyaka et al., 2015), and fourth in tropical and subtropical regions, supporting the livelihoods of over 700 million people (Sanginga, 2015). In Cameroon, root and tuber crops make up 70% of cultivated land and account for 46% of food crop output, with cassava production reaching approximately 2.9 million tons in 2008 (Agristat, 2009). Despite its importance as a staple carbohydrate source (FAO, 2021), cassava cultivation is severely challenged by numerous diseases that reduce yield and quality Cassava production faces serious risks from Cassava mosaic disease (CMD) and cassava brown streak disease (CBSD), which results in considerable economic harm (Naylor et al., 2020). Similarly, bacterial blight poses a major risk and can result in complete crop destruction (Machado et al., 2014). In Africa, several fungal pathogens also contribute to yield decline, including Fusarium species responsible for dry rot (F. solani, F. oxysporum, and F. verticillioides); Phytophthora species such as P. nicotianae and P. drechsleri, and Pythium scleroteichum, which cause soft rot; and Neoscytalidium hyalinum and Lasiodiplodia species, associated with black rot (Machado et al., 2014). Among insect pests, whiteflies are particularly destructive across all cassava-growing regions, while mealy bugs and cassava mites damage plants by injecting toxins that lead to leaf wilting (Machado et al., 2014). Soil physicochemical characteristics, such as pH, nutrient content, organic matter, and texture, play an important role in plant health and disease development. Soil pH, for instance, influences nutrient availability and microbial activity, which can impact the occurrence of diseases caused by bacteria and fungi (Otaiku et al., 2019). Studies show that specific soil conditions can either inhibit or promote the growth of harmful pathogens, thereby affecting cassava plant health (Otaiku et al., 2019). The interaction between soil characteristics and rhizospheric microbes is key, as beneficial microbes support nutrient uptake and plant development, while harmful microbes thrive under poor soil conditions and exacerbate disease severity (Li et al., 2021). Soil physicochemical properties such as pH, organic matter content, nutrient levels, and soil texture, influence the incidence and severity of fungal diseases in plants (Bailey and Lazarovits, 2003). For example, high soil organic matter content supports beneficial microbes capable of supressing pathogens. Studies have shown that modifying soil properties can be an effective strategy for managing soil-borne fungal diseases (Bailey and Lazarovits, 2003). Also, elevated soil organic carbon is a key factor in the prevalence of fungal plant pathogens in agricultural soils (Du et al., 2022) while soil pH has a significant impact on the incidence and severity of several plant diseases, potentially by changing nutrient availability and influencing fungal community richness (Mahmood and Bashir, 2011). This research aims to investigate the pathogenicity of fungal species affecting cassava and to evaluate how variations in soil physicochemical properties influence the incidence and severity of fungal disease in cassava farms in Bamenda, Cameroon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

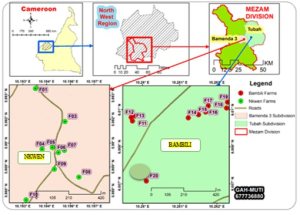

Study site: Bamenda is situated in Mezam Division, Northwest Region, Cameroon. It is located at the center of the Cameroon volcanic line, lying beneath the high lava plateau, at an altitude between 1100-1500 m above sea level (Acho, 1998), latitude 5.5734N and longitude 10.845E The climate is primarily of the equatorial monsoonal variety, known for significant rainfall and elevated humidity, consisting of two main seasons; a prolonged rainy (wet) season that lasts for 7.5 months Between mid-March and early November, there is about a 45% likelihood of experiencing rain on any given day, while the dry season lasts for 4.5 months from early November to mid-March. The yearly average rainfall varies between 1,700 and 2,824 mm and shows some variability (Ayonghe, 2001). The months of January to April have average high temperatures between 25.9°C to 25.6°C, average low temperatures between 13.2°C to 16.7°C, average rainfall between 11.6 to 178.1 and average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) (Ayonghe, 2001). As noted by Morin (1988), Bamenda is part of the West Cameroon Highlands, which is the region’s most significant geomorphological system. The Bamenda Mountains feature a basement rock largely consisting of Precambrian leucogranite, with volcanic materials, including mafic and felsic lavas, layered on top(Nzenti et al., 2010; Gountie et al., 2012). The process of chemical weathering acting on the basement and the resulting volcanic rocks generates sediments composed of particles from clay to sand size (Asaah et al., 2013) with the major clay minerals identified as montmorillonite (Mache et al., 2013). Bamenda is characterized by fractured phreatic superimposed aquiferous formations (Keleko et al., 2013). The majority of the city’s population speaks English, while Pidgin English is the predominant language heard in the shops and on the streets of Bamenda.Bamenda city is composed of three villages: Mankon, Nkwen and Bamendankwe. It is, however, surrounded by additional suburban areas and villages like Bambui, Bambili, Akum, Bafut, Bali, Chombah, and Mbatu (WUP, 2011) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Map of study area showing sampling plots (Nkwen and Bambili)

Identification of fungi species: The identification of fungi was done through cultural and molecular identification methods. Cultural characteristics of isolates, including colony diameter, elevation, margins, and colour, were recorded according to the methods of Wantanabe (2002) and molecular identification was done with reference to Lem et al. (2024). Among the 32 species identified, five most prevalent fungi isolates were selected for pathogenicity test.

Assessment of fungal pathogens associated with cassava in Bamenda: A pathogenicity test was conducted in a greenhouse located at the Bamenda University of Science and Technology (BUST) campus. The greenhouse was thoroughly cleaned and sterilized using 5% sodium hypochlorite and 95% alcohol to ensure a controlled environment. For the experiment, 100 healthy-looking cuttings of a local cassava variety (TME 419) were collected from the Exemplary Mixed Farming Cooperative Society Limited in Bambili and used for pathogenicity test.

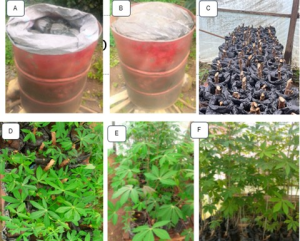

Soil sterilization for pathogenicity test: Topsoil from a depth of 0–10 cm was collected from the BUST research farm using a hand trowel and then heat-sterilized for use in the experiment. The sterilization process involved placing a 45 cm tripod stand inside a drum set over a heat source. Water was added to the drum, just below the tripod level. Biodegradable bags filled with the collected topsoil were placed on the tripod and covered with thick jute sacks to retain heat. The drum was sealed tightly with plastic and secured with rope. Heat was applied continuously for two hours from the boiling point. After sterilization, the cover was removed, and the soil was allowed to cool to approximately 30°C before being transferred to the greenhouse. Sterilized soil was packed into perforated plastic bags measuring 30 × 12 cm and moistened with tap water. Eighty cassava cuttings (15 cm each, with at least three nodes) were planted in the sterilized soil, while 20 additional cuttings were placed in bags containing unsterilized soil. All bags were arranged on a greenhouse table at an ambient temperature of 30°C ± 2. During the first three days, the plants were watered daily until saturated, after which they were watered twice a week for 16 weeks. Observations were regularly made for growth performance and disease symptoms for 6 weeks (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Process of cassava growth in the greenhouse. A and B) Soil sterilization in a drum C) Cassava cuttings in perforated plastic bags, D) 3 weeks after planting, E) 8 weeks after planting, F) 16 weeks after planting (Azinue et al., 2023).

Preparation of potato dextrose broth: Two hundred grams of unpeeled potato tubers were washed, sliced, and boiled in 1000 ml of distilled water for 45 minutes. The mixture was then drained using cheesecloth, and the liquid extract was collected in a beaker. Twenty grams of commercial dextrose was measured and dissolved in the potato extract. . To bring the volume back to 1,000 ml, sterile distilled water was added. An autoclave was used to sterilize the final solution at 121°C for 15 minutes.

Preparation of inoculum: The inoculum was prepared from fresh 7-day old cultures of the five most prevalent fungi isolates (Trichoderma harzarium, Fusarium oxysporum, Colletotrichum boninense, Aspergillus pallidofulvus and Geotrichum candidum) (gotten from the preserved pure cultures) and grown in potatoes dextrose broth (PDB). After 2 days of incubation, the bottles were shaken to disperse the hyphae and the cultures were allowed to grow for 14 days. Each dish was flooded with 5ml of sterile distilled water and spores dislodged with a sterile inoculation needle. The spore suspension for each isolate was separately filtered through double layers of cheesecloth to remove mycelia fragments and stalling materials, then adjusted to 104 conidia/ml with the aid of a haemocytometer and tally counter. This was stored in 100ml test tubes in a refrigerator in duplicates before inoculation. This was according to the methods of Wokocha et al. (2010).

Inoculation: After 16 weeks, 30 cassava plants with similar stem height and leaf size were selected from the 80 grown cassava in sterilized soil. Selection was based on the absence of visible disease symptoms and signs of nutrient deficiency. These plants were divided into six groups, each containing five plants (with five replicates), and labelled T1 to T6 to represent six treatments. Using a sterile blade, four incisions were made on the stems at various internodes for inoculation via stem injection (Figure 3). A sterile syringe was used to inject 10 ml of a fungal suspension (10⁴ conidia/ml) into each treatment, delivering 0.5 ml per incision or 2 ml per plant (Figure 3). Inoculations were carried out in the evening to maximize exposure to high humidity conditions. Control plants were injected with 2 ml of sterile distilled water. The experiment was carried out in a greenhouse maintained at a temperature of 30 °C ± 2 for 22 weeks. Disease symptoms were monitored weekly for six weeks, starting from inoculation until the appearance of the first visible signs. The procedure was adapted from Kinge et al. (2023). Additionally, five cassava plants from unsterilized soil were observed to check for any soil borne inoculum. A randomized complete block design (RCBD) was utilized for the experiment, consisting of six treatments and five replicates.The progression of disease symptoms on cassava leaves was measured weekly for six weeks. Observed symptoms were compared to those found on cassava leaves from farmers’ fields. After six weeks, symptomatic leaves were collected for fungal re-isolation and identification on potato dextrose agar (PDA), following the method described by Nakarin et al. (2022).

Figure 3: Inoculation of cassava plants grown in the greenhouse A) treatment group B) stem incision C) inoculation by stem injection method (Azinue et al., 2023).

Assessment of pathogenicity: Pathogenicity was evaluated by observing the symptoms caused by each fungal pathogen on the inoculated cassava plants. A transparent ruler was used to measure the lengths of lesions that appeared on the stems each week over a six-week durationThe average lesion length for each fungal isolate was determined and utilized for data analysis. Disease severity was rated using a 1 to 5 scale, following a method similar to that described by Waller and Jeger (1998) where:

1=0 mm (no lesion),

2= – 5 mm lesion size,

3 =6 – 10 mm lesion size,

4 =11 – 25 mm lesion size,

5 = more than 25 mm lesion size.

Koch’s postulate was applied by re-isolating fungi from the symptomatic leaf tissues and culturing them on freshly prepared PDA. The identity of the re-isolated fungi was confirmed based on their morphological characteristics on the culture medium. The method used was consistent with the procedure detailed by Nakarin et al. (2022).

Evaluation of disease intensity (incidence and severity) of cassava: Field surveys were carried out from October to December 2021 to evaluate the variation in fungal disease symptoms affecting cassava in farmer’s farms in Bamenda. From February to March 2022, 20 cassava farms, 10 each in Nkwen and Bambili, were selected through opportunistic sampling. Only secondary cassava fields older than six months were considered. Fifty cassava plants were sampled per farm following the method of Nyaka et al. (2015). At each site, observations were made on disease symptoms and GPS data (latitude, longitude, and altitude) were recorded using a Garmin Etrex R30 to generate a GIS map of surveyed locations. Farmers provided crop age, and field size was estimated by visually counting cassava stems. The cassava variety, local or improved was documented. The number of plants exhibiting fungal symptoms such as brown leaf spot, angular leaf spots, chlorosis, powdery leaf surfaces, and general wilting was recorded per farm to calculate disease incidence. Plants damaged by insects were excluded. Disease incidence was expressed as a percentage of infected plants relative to total plants assessed.

Disease incidence:

number of infected plants ÷ total number of plants assessed

Percent incidence:

number of infected plants ÷ total number of plants assessed ×100

The assessment of disease severity was conducted using the 1 to 5 severity scale from the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA, 1990) where 1 represents no symptoms and 5 the most severe disease symptoms. The scale was rated as follows:

1= no disease symptom;

2 = shallow cankers on stems, lower down the plants;

3 = successive cankers higher up the plant with cankers on older stems becoming larger and deeper and light brown leave spots;

4 = dark-brown lesions on green shoots, petioles and leaves, young shoots collapsed and distorted;

5 = wilting, drying up of shoots and young leaves, and death of part or whole plant. (Mwangi et al., 2004).

Investigation of soil physicochemical properties on fungal disease intensity

Soil Sampling and Collection: Soil samples were collected from 20 cassava farms in Bamenda (10 farms each from Nkwen and Bambili) using a soil auger. The soils collected from Nkwen were coded as AC1-AC10 while soil samples collected from Bambili were coded as AC11-AC20. Sampling was carried out at the rhizosphere (the soil surrounding cassava roots) at four levels of disease incidence: none, low, moderate, and high. To prevent cross-contamination between sites, sampling tools were disinfected with 5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), and samples were processed separately. For each disease incidence level within a farm, ten soil samples were collected from different locations (0-10cm depth), placed in labelled zip-lock bags, and bulked. Every sample was taken in duplicate, and the coordinates of each sampling point were recorded using a Global Positioning System (GPS). These coordinates were later used to create a Geographic Information System (GIS) map of the sampled cassava farms.

Soil preparation: The collected soil samples were spread in plastic trays and allowed to air dry for four days, avoiding direct sunlight. During this process, labels were carefully maintained. Large soil clumps were crushed, and plant debris was removed. Once dried, the soil was passed through a 2mm sieve to eliminate gravel and rock particles that could not pass through. The resulting uniform soil was weighed using an electronic balance. A portion of 250 grams was measured, placed into zip-lock bags in duplicate, properly labelled, and then transported in a cooler to the Science Laboratory at the University of Dschang for nutrient content analysis.

Soil physicochemical characterization: The soil samples were examined for their physical and chemical properties. The parameters measured included: soil pH in water and in potassium chloride (pH KCl), percentages of clay, silt, and sand, organic carbon (OC%), organic matter (OM%), nitrogen (N%), phosphorus (P in mg/kg), carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C/N), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), and potassium (K) in meq/100g, sum of base exchangeable cations (SBE), cation exchange capacity (CEC), and base saturation percentage. The pH values were measured using the potentiometric method (ISRIC, 2002). Soil texture, which comprises clay, silt, and sand, was analyzed through the pipette method. Organic carbon and matter content were evaluated using the Walkley-Black method at 125°C following Nelson and Sommers (1982). The Kjeldahl method described by Jones (2001) was used to measure total nitrogen, while available phosphorus was determined using Olsen’s method (1954). Calcium and magnesium were analyzed using flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS), and potassium and sodium were measured with flame emission spectrophotometry (FES). Cation exchange capacity was determined using the mechanical extraction method by Abera and Kefyalew (2017).

Assessment of pathogenicity: The five isolates selected were found to be pathogenic on the local variety of cassava grown in the greenhouse. These isolates showed various symptoms on the cassava including necrotic lesions on leaves and at the points of inoculation on cassava stems, brown to grey leaf spots, patches of discolouration (chlorosis), distortion and yellowing of leaves. Lesser lesion damage was also observed on two of the five control plants inoculated with sterile distilled water. Though the lesions produced on these control plants were smaller (0.2cm) and did not expand further as the experiment progressed to the 6th week, as compared to the infected lesions that were different, bigger and expanded slowly but progressively to various spot sizes as the week progressed (Table 1).

Table 1: Parameters gotten from cassava plants grown in the greenhouse

| Treatment | Treatment identity | Disease incidence/5

(week 1-6) |

Disease severity (week 1-6) | Average lesion length

per week (cm) |

Average lesion length/6weeks (cm) | |||||||||||||||

| T1 | Trichoderma harzarium | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.47 |

| T2 | Fusarium oxysporum | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.72 |

| T3 | Colletotrichum boninense | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.28 |

| T4 | Aspergillus pallidofulvus | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.20 |

| T5 | Geotrichum candidum | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.22 |

| T6(control) | Sterile distilled water | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.07 |

| T7 | Unsterilized soil | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.60 |

Results showed that, within one week of inoculation, only one isolate (Fusarium oxysporum) produced disease symptom on cassava leaves (brown leaf spot) while the other isolates showed the first symptom at the second week or after two weeks from the day of inoculation. Also, there was a gradual increase in the size of lesions produced on infected plants from week 1 to 6 after inoculation. Assessment of disease incidence and severity on infected plants showed a progressive increase as the weeks go by. The highest incidence (0.8) was recorded by the isolate Fusarium oxysporum, while the least incidence (0.4) was recorded from Colletotrichum boninense and Aspergillus pallidofulvus. On a 1–5-point scale, Fusarium oxysporum still recorded the highest disease severity score (3) followed by Colletotrichum boninense with a severity score of (2), while the other isolates scored 1 each for Cassava disease incidence and severity in Nkwen and Bambili.

Field symptoms associated with cassava plants: Fungal symptoms on cassava leaves were consistent across both study locations. Infected leaves commonly exhibited brown spots with defined edges on both surfaces. The upper surfaces showed dark-bordered spots, whereas the lower surfaces had less distinct margins. These lesions ranged from 2 to 13 mm in diameter and usually halted at major veins or the leaf’s edge. Some leaves featured larger, poorly defined brown patches covering 10–20% of the leaf surface, uniformly brown on top and brown to grey underneath. Irregular white to yellow spots, 2–6 mm wide, were also noted, with affected areas appearing thinner than healthy tissue. Additional symptoms included large, dark brown lesions with unclear borders along lobes, edges, or midribs, often becoming necrotic with black streaks on the underside. Older leaves showed more resistance, while younger leaves were more prone to damage, including partial dieback and defoliation. Several cassava plants showed multiple disease symptoms simultaneously, while others experienced other plant effects such as stunted growth and significant leaf loss. Yellowing of leaves was commonly observed in all symptomatic plants. The most encountered symptoms included brown leaf spots, angular leaf spots, and chlorosis. The symptomatic cassava stems showed signs of dark spots (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Field Symptoms observed on cassava leave and stems in farmers’ farms in Nkwen and Bambili. A,B,C) Brown leaf spot, D) Angular leaf spot, E,F) leaf mosaic G) asymptomatic stems, H) light dark spots, I) dark spots (Field work, 2022).

Fungal disease incidence and severity in the cassava farms: On average, cassava disease incidence was relatively low in both Nkwen (0.226) and Bambili (0.428), with Bambili showing slightly higher levels. In Nkwen, disease incidence ranged from 0.22 to 0.50, while in Bambili, it ranged from 0.12 to 0.66 (Table 2), indicating a higher incidence in Bambili. The overall disease severity across both locations, based on the disease severity rating scale, averaged 2.55 (approximately 3), indicating mild disease severity. Specifically, Nkwen recorded a lower average severity of 2.4, while Bambili had a slightly higher severity value of 2.7 though still considered low.

Table 2: Disease incidence and severity obtained from cassava farms in Nkwen and Bambili

| Locality | Cassava farm (F) | Disease incidence | Percentage incidence (%) | Disease severity scale | Latitude | Longitude | Altitude |

| Nkwen | F01 | 0.22 | 22 | 2 | 05059.608′ | 10011.628′ | 1257m |

| Nkwen | F02 | 0.20 | 20 | 2 | 05059.506′ | 10011.720′ | 1259m |

| Nkwen | F03 | 0.14 | 14 | 2 | 05059.492′ | 10011.731′ | 1265m |

| Nkwen | F04 | 0.10 | 10 | 2 | 05059.395′ | 10011.651′ | 1252m |

| Nkwen | F05 | 0.08 | 08 | 2 | 05059.401′ | 10011.687′ | 1260m |

| Nkwen | F06 | 0.26 | 26 | 3 | 05059.383′ | 10011.708′ | 1271m |

| Nkwen | F07 | 0.50 | 50 | 3 | 05059.391′ | 10011.729′ | 1270m |

| Nkwen | F08 | 0.12 | 12 | 2 | 05059.297′ | 10011.780′ | 1287m |

| Nkwen | F09 | 0.30 | 30 | 3 | 05059.325′ | 10011.694′ | 1261m |

| Nkwen | F10 | 0.34 | 34 | 3 | 05059.217′ | 10011.595′ | 1279m |

| Bambili | F11 | 0.12 | 12 | 2 | 06000.569′ | 10015.567′ | 1435m |

| Bambili | F12 | 0.24 | 24 | 2 | 06000.566′ | 10015.558′ | 1433m |

| Bambili | F13 | 0.64 | 64 | 4 | 06000.558ʹ | 10015.561ʹ | 1433m |

| Bambili | F14 | 0.56 | 56 | 3 | 06000.565′ | 10015.686′ | 1458m |

| Bambili | F15 | 0.20 | 20 | 2 | 06000.572′ | 10015.709′ | 1454m |

| Bambili | F16 | 0.48 | 48 | 3 | 06000.578′ | 10015.725′ | 1460m |

| Bambili | F17 | 0.66 | 66 | 4 | 06000.592′ | 10015.731′ | 1455m |

| Bambili | F18 | 0.48 | 48 | 3 | 06000.587′ | 10015.772′ | 1457m |

| Bambili | F19 | 0.66 | 66 | 3 | 06000.600′ | 10015.774′ | 1457m |

| Bambili | F20 | 0.24 | 24 | 2 | 06000.423′ | 10015.592′ | 1433m |

Effect of soil physicochemical properties on the intensity of fungal diseases of cassava: Soil physicochemical properties: The physical properties of the soil were the same while there was a variation in the chemical properties of soils collected from 20 cassava farms in Bamenda. In terms of physical properties, clay, silt and sand showed same values (27.00%, 20.55%, and 52.50% respectively) across both sites. The findings from the different research farms suggest that the physical properties of the soils were consistent across both locations. . With regard to soil chemical properties, soil pH water, phosphorus (P(mg/kg)) and carbon/nitrogen (C/N) content varied within the farms with the highest values recorded in Nkwen at farm AC10 (6.6), AC7 (113.19) and AC10 (105.26) respectively and least values recorded in Nkwen (for pH water) and Bambili at AC1 (5.1), AC16 (4.29) and AC12 (5.75) respectively. The soil organic concentration (OC %), organic matter (OM %), and nitrogen percentage (N %) also varied within the farms. The highest values were recorded both in Nkwen and Bambili at farm AC5 and AC15 (5.31, 9.15 and 0.133) respectively and lowest values recorded in Nkwen at farm AC09 (2.72, 4.69 and 0.406 respectively). The soil calcium (Ca (méq /100g)), magnesium (Mg (méq /100g)), potassium (k (méq /100g)) and sodium (Na (méq /100g) were also found in varied concentrations across the farms. The maximum values were observed in Nkwen at farm AC1 (4.91), AC7 (2.8), AC3 (1.58) and AC8 (0.08) respectively while least values were recorded at both sites AC4 or AC15 (1.09), AC7 (0.26), AC15 (0.01) and AC3 (0.01) respectively. The soil’s pH ranged from 4.0 to 6.6 across the farms. Variation in the physicochemical properties of soils across farms are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3: Physicochemical characteristics of soil samples from 20 cassava farms in Bamenda

| Code | pH

Water |

pH K

Cl |

Clay

% |

Silt

% |

Sand

% |

OC

% |

OM

% |

N% | P(mg

/kg) |

C/N | Ca

(méq /100g) |

Mg

(méq /100g) |

K

(méq /100g) |

Na

(méq /100g) |

SBE

(méq/ 100g) |

CEC

(méq/ 100g) |

Base

satura tion% |

| AC1 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 3.12 | 5.37 | 0.035 | 52.31 | 89.02 | 4.91 | 1.73 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 6.73 | 14.96 | 44.97 |

| AC2 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 2.78 | 4.79 | 0.266 | 50.66 | 10.45 | 2.91 | 1.09 | 0.86 | 0.03 | 4.89 | 13.56 | 36.06 |

| AC3 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 3.79 | 6.53 | 0.231 | 24.46 | 16.4 | 2.45 | 0.55 | 1.58 | 0.01 | 4.6 | 13.8 | 33.31 |

| AC4 | 5.6 | 4.5 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 3.4 | 5.86 | 0.245 | 41.45 | 13.86 | 1.09 | 0.51 | 0.86 | 0.03 | 2.49 | 12.88 | 19.33 |

| AC5 | 5.5 | 4.4 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 5.31 | 9.15 | 0.133 | 40.86 | 39.89 | 2.00 | 0.56 | 1.25 | 0.03 | 3.84 | 15.84 | 24.22 |

| AC6 | 6.1 | 5.0 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 4.01 | 6.92 | 0.441 | 37.32 | 9.1 | 3.55 | 2.85 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 6.67 | 15.9 | 41.93 |

| AC7 | 5.6 | 4.4 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 4.8 | 8.28 | 0.2275 | 113.19 | 21.1 | 3.82 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 4.29 | 15.2 | 28.24 |

| AC8 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 3.96 | 6.82 | 0.441 | 102.69 | 8.97 | 2.55 | 1.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 3.72 | 13.28 | 28.02 |

| AC9 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 2.72 | 4.69 | 0.406 | 81.45 | 6.71 | 2.73 | 0.47 | 0.68 | 0.04 | 3.92 | 15.16 | 25.88 |

| AC10 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 2.95 | 5.08 | 0.028 | 99.98 | 105.26 | 2.91 | 1.09 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 4.46 | 13.32 | 33.46 |

| AC11 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 3.12 | 5.37 | 0.49 | 97.5 | 6.36 | 2.27 | 1.25 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 3.91 | 13.6 | 28.76 |

| AC12 | 6.0 | 4.8 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 2.78 | 4.79 | 0.483 | 41.69 | 5.75 | 5.64 | 1.16 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 7.42 | 14.6 | 50.80 |

| AC13 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 3.79 | 6.53 | 0.364 | 24.23 | 10.41 | 3.82 | 1.38 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 5.81 | 14.76 | 39.39 |

| AC14 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 3.4 | 5.86 | 0.574 | 39.8 | 5.92 | 3.18 | 1.42 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 5 | 13.36 | 37.45 |

| AC15 | 6.0 | 4.7 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 5.31 | 9.15 | 0.476 | 13.72 | 11.15 | 1.09 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1.63 | 13.52 | 12.09 |

| AC16 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 4.01 | 6.92 | 0.616 | 4.29 | 6.52 | 4.73 | 1.27 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 6.28 | 14.4 | 43.58 |

| AC17 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 4.8 | 8.28 | 0.476 | 27.41 | 10.08 | 4.73 | 1.67 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 6.55 | 12.48 | 52.51 |

| AC18 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 3.96 | 6.82 | 0.511 | 17.5 | 7.75 | 3.36 | 1.04 | 0.86 | 0.03 | 5.28 | 13.45 | 39.28 |

| AC19 | 5.6 | 4.5 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 2.72 | 4.69 | 0.322 | 12.07 | 8.46 | 2.73 | 0.47 | 0.68 | 0.04 | 3.92 | 13.92 | 28.19 |

| AC20 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 27 | 20.5 | 52.5 | 2.95 | 5.08 | 0.357 | 10.89 | 8.26 | 2.91 | 1.09 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 4.46 | 13.2 | 33.76 |

Soil analysis: The soil properties were analysed using Pearson correlation analysis at two probability levels (p 0.05 and p0.01). The analysis revealed that, there was a moderate positive correlation of 0.577*(p < 0.05) between pH in water and pH in KCl, indicating that, an increase in pH of water content of the soil will also lead to an increase in pH KCl content. This reflects consistent measurement methods for acidity/alkalinity. A very strong positive correlation of 0.963**(p < 0.01) was found between organic carbon (OC %) and organic matter (OM %), suggesting that higher organic carbon levels correspond to greater organic matter content in the soil. Conversely, there was a moderate negative correlation of -0.392 (p < 0.05) between OC% and base saturation, indicating that increased organic carbon may lead to reduced levels of exchangeable bases. Additionally, a strong positive correlation of 0.886** (p < 0.01) was observed between calcium and base saturation, essential for evaluating soil fertility. Magnesium levels showed a moderate positive correlation of 0.515* (p < 0.05) with cation exchange capacity (CEC), highlighting its importance for nutrient availability. However, a moderate negative correlation of -0.366 (p < 0.05) was noted between nitrogen and phosphorus, suggesting potential competition for nutrient uptake. Lastly, there was no significant correlation (0.000) between sodium levels and base saturation, indicating that sodium does not affect base saturation (Table 4).

Table 4: Pearson correlation analysis for soil samples

The comparison of soil parameters between Nkwen and Bambili revealed that, there were several significant differences that existed between both soils (Table 5). Soil samples from Nkwen exhibited a pH water range of 5.1 to 6.6, while those from Bambili varied from 4.8 to 6.0 indicating a significant difference. Conversely, the pH KCl values for Nkwen ranged from 4.0 to 5.4, whereas those for Bambili ranged from 4.0 to 4.9, indicating that Bambili soil samples had higher acidity levels. In terms of Organic Carbon (OC %), Nkwen had values ranging from 2.72 to 5.31, while Bambili had values between 2.78 to 5.31; although the maximum values were similar, the lower values showed no significant difference overall. Regarding Organic Matter (OM%), it ranged from 4.69 to 9.15 in Nkwen which was slightly higher on average than Bambili’s range of 4.79 to 9.15, yet both locations showed comparable maximum values. Furthermore, calcium levels were significantly higher in Nkwen, with values between 2.49 and 105.26 compared to Bambili’s range of 1.63 to 11.15, while magnesium values in Nkwen ranged from 0.01 to 4.91, slightly higher than Bambili’s values from 0.01 to 4.73. Additionally, nitrogen levels were generally higher in Bambili. The nitrogen values for Nkwen ranged from 0.028 to 0.441 and Bambili’s values from 0.364 to 0.616, indicating significant differences in the soil’s nitrogen contents. Lastly, phosphorus levels were significantly higher in Nkwen, ranging from 24.46 to 113.19, while Bambili samples ranged from 4.29 to 97.5, and Nkwen’s base saturation ranged from 19.33 to 44.97, in contrast to Bambili’s range of 12.09 to 50.80, indicating that, Bambili had a higher base saturation capacity.

Table 5: Relationships between soil parameters from Nkwen and Bambili

| Soil Parameter | Nkwen range | Bambili range | P-Value | Significance |

| pH Water | 5.10 – 6.60 | 4.80 – 6.00 | < 0.05 | Significant |

| pH KCl | 4.00 – 5.40 | 4.00 – 4.90 | < 0.05 | Significant |

| Organic Carbon (OC %) | 2.72 – 5.31 | 2.78 – 5.31 | 0.687 | Not Significant |

| Organic Matter (OM %) | 4.69 – 9.15 | 4.79 – 9.15 | 0.587 | Not Significant |

| Calcium (Ca) | 2.49 – 105.26 | 1.63 – 11.15 | < 0.01 | Significant |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 0.01 – 4.91 | 0.01 – 4.73 | 0.638 | Not Significant |

| Nitrogen (N %) | 0.028 – 0.441 | 0.364 – 0.616 | < 0.05 | Significant |

| Phosphorus (P mg/kg) | 24.46 -113.19 | 4.29 – 97.50 | < 0.01 | Significant |

| Base Saturation (%) | 19.33 – 44.97 | 12.09 – 50.80 | 0.295 | Not Significant |

Correlation between soil physicochemical properties and disease incidence and severity in Nkwen and Bambili: The Pearson correlation coefficient between pH KCl and disease severity was 0.497, with a significance level of 0.026, indicating a moderate positive correlation; thus, higher pH levels (in KCl) are associated with increased disease severity, statistically significant at p=0.05. Additionally, there was a strong positive correlation between disease incidence and severity, with a coefficient of 0.642, statistically significant at p= 0.001. In contrast, the correlation between organic carbon (OC %) and disease severity is 0.286, but this is not considered statistically significant. (p = 0.222), indicating that OC% does not significantly influence disease severity. Similarly, nitrogen (N %) shows a correlation of 0.255 with disease severity, which is also not statistically significant (p = 0.277), This suggests that there is a weak relationship between nitrogen levels and disease outcomes. . The correlation between phosphorus levels and disease incidence was negative at -0.314, but this is not considered statistically significant. (p = 0.177), indicating a weak inverse relationship where higher phosphorus levels may be associated with lower disease incidence. Lastly, the C/N ratio demonstrates weak negative correlations with both disease incidence (-0.214) and severity (-0.043), with p-values of 0.365 and 0.858, respectively. This showed that, the soil’s C/N ratio didn’t have a major influence on disease intensity (Table 6).

Table 6: Correlation between soil physicochemical properties and disease intensity (incidence and severity)

| Correlations | pH KCl | Clay% | Silt % | Sand% | OC% | N% | P(mg/kg) | C/N | Disease incidence | Disease severity scale |

| pH KCl

OC% N% P(mg/kg) C/N Disease incidence Disease severity scale |

1 | |||||||||

| .183 | .a | .a | .a | 1 | ||||||

| -.057 | .a | .a | .a | -.018 | 1 | |||||

| -.093 | .a | .a | .a | -.102 | -.328 | 1 | ||||

| .023 | .a | .a | .a | -.136 | -.203 | .329 | 1 | |||

| .102 | .a | .a | .a | .032 | .140 | -.314 | -.214 | 1 | ||

| .497* | .a | .a | .a | .286 | .255 | -.035 | -.043 | .642** | 1 | |

| *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). | ||||||||||

| **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | ||||||||||

| a. Cannot be computed because at least one of the variables is constant. | ||||||||||

DISCUSSION

Pathogenicity studies identified several fungal species, including: Aspergillus pallidofulvus, Colletotrichum boninense, Fusarium oxysporum, Geotrichum candidum and Trichoderma harzarium which have been previously reported to have an influence in plant health and cause diseases of cassava. They either promote plant growth through nutrient acquisition or cause diseases that affect yield (Santos et al., 2020). These results support earlier studies that highlight Fusarium spp. . are major contributors to root and stem rot, while Colletotrichum is known to cause anthracnose in cassava (Ogweno and Karanja, 2018; Nwankwo and Okeke, 2021). The pathogenicity of Fusarium oxysporum, is concerning as it is linked to root rot and other diseases in cassava (Ogweno and Karanja, 2018). Previous reports showed that the genus Fusarium is associated with soft rot of cassava (Theberge, 1985). The genus Fusarium and Trichoderma, have been previously reported in cassava farms in Cameroon and in Ethiopia to cause cassava root rot (Nyaka et al., 2015; Berhanu, 2017). Previous studies carried out by Nyaka et al. (2015) in Cameroon on fungal species associated with cassava revealed that, among the species found, seven were pathogenic and caused cassava root rot disease which included species of Colletotrichum, Fusarium, Pestalotia, Geotrichum, Shaerostilbe, Trichoderma, and Botryodiplodia. Also, Berhanu (2017) carried out a related study on fungal pathogens associated with cassava diseases in Southeast Ethiopia and reported that, there was a diversity of fungi species associated with cassava while the genus Fusarium, recorded the highest number in terms of diversity, disease incidence and severity in cassava fields. Nia et al. (2020) also reported that, among the fungi pathogens of cassava, the greatest diversity is found in the genus Fusarium, Trichoderma and Colletotrichum. Damages caused by the genus Colletotrichum on cassava have also been reported by Nyaka et al. (2015). Colletotrichum gloesporioides f. sp. Manihotis is known to cause anthracnose diseases on cassava (Magdalena et al., 2012) which is an important disease of cassava in tropical Africa, transmitted through breeder seeds and postharvest debris in the field (Fokunang et al., 2001). It has been reported that the disease can result in total crop loss if infected propagation materials are used as seeds (Magdalena et al., 2012). Geotrichum sp. has been previously reported to be involved in fermentation and postharvest deterioration of tubers and roots of cassava (Oyewole and Odunfa, 1988). Some fungal species such as Fusarium spp. and Aspergillus sp. can produce mycotoxins that can contaminate food supplies, posing risks to human health (Pitt and Hocking, 2009). The variability in pathogenicity among the different isolates suggest that, genetic diversity within fungal populations may influence virulence. For instance, the isolate of Fusarium exhibited higher pathogenicity, resulting in greater disease severity and faster symptom development compared to others. Fusarium and Colletotrichum species are known for their pathogenic potential, aligning with earlier reports linking these genera to cassava anthracnose and root rot diseases (Ogunsola and Ayansina, 2019). Pathogenicity test revealed varying degrees of virulence among the tested fungal species. The results confirm that certain fungal isolates are capable of inducing disease symptoms characteristic on cassava leaves, such as brown leaf spot, and angular leaf spots. Among the isolates tested, Fusarium oxysporum and Trichoderma harzarium demonstrated the highest pathogenicity, as evidenced by leaf symptoms, yellowing and leaf wilting. These findings are consistent with previous reports that identified Fusarium solani as a major causal agents of cassava disease in tropical and subtropical regions (Okereke et al., 2017; Onyeka et al., 2018). The fast progression of symptoms after inoculation suggests an aggressive colonization strategy by these fungi, possibly involving the secretion of cell wall degrading enzymes and mycotoxins (Abiala et al., 2015). In contrast, isolates of Colletotrichum boninense, Aspergillus pallidofulvus and Geotrichum candidum caused milder symptoms. This may suggest that these fungi are either weak pathogens or opportunistic colonizers, thriving in damaged cassava tissues. The degree of pathogenicity observed may have also been impacted by environmental factors, including temperature, humidity, and soil composition. Cassava plants grown under humid conditions have been reported to be more susceptible to fungal infections due to increased leaf wetness and favourable conditions for spore germination (Ezedinma et al., 2014). The Koch’s postulates were fulfilled during this study, as the symptoms induced by the fungal isolates in the inoculated plants were similar to those observed in naturally infected cassava samples, and the same fungi were successfully re-isolated. This confirms the causal relationship between the fungal isolates and the observed disease symptoms. Identifying pathogenic species can inform breeding programs aimed at developing resistant cassava varieties and guide farmers in implementing targeted fungicidal treatments or cultural practices to reduce inoculum build-up in the field. The higher disease incidence and severity observed in Bambili could be attributed to a greater diversity of fungal species, higher altitude, or specific soil-related (edaphic) conditions in the area. The slightly acidic soils of the various farmlands could be as a result of weathering of rocks in the farmlands leading to the breakdown of minerals, thus releasing acids that lower the soil pH. It can also be due to the decomposition of organic matter by soil microbes such as bacteria, releasing organic acids that contributes to soil acidity. The use of fertilizers can also lead to increase soil acidity overtime as it breaks down. The low clay and silt percentages could be due to the geological origin of the soil as soils formed from sand-rich parent material will naturally have lower silt and clay content. The average sand percentage of the soil may as a result of sandy parent material (sandstone or river sediments) and weathering of rocks. The percentage of organic carbon and organic matter between 2.72 to 5.31 and 4.69 to 9.15 respectively may be as a result of grassland vegetation of the farmland and microbial action on the organic matter present. The overall low levels of the soil bases (calcium,) can result from leaching due to heavy rainfall that wash away these bases and soil erosion. The incidence and severity of fungal diseases of cassava pose a challenge to crop productivity and food security in regions where this staple crop is cultivated. The less disease severity of fungal diseases of cassava, with the most prevalent field symptoms being leaf spot and stem dark spots could be as a result of leaf spot disease of cassava and cassava anthracnose disease. This finding aligns with previous research that reported significant levels of Colletotrichum associated with cassava plants, leading to leaf spot disease of cassava (Nwankwo and Okeke, 2021). The variations observed in the severity of infections across the different farmlands, shows the ability of some cassava plants to prevent the entry of fungi pathogens in to its tissues. Also, the slightly longer rainy season in Bambili, can account for the disease intensity observed in the field. This corroborates the finding of Kakuhenzire and Karamura (2020) who reported a positive correlation between rainfall and humidity levels with higher disease incidence. Soil pH affects fungal disease incidence and severity in cassava. Mengel and Kirkby (1987) recommend sites with a high percentage of clay and silt for farming, as they can effectively provide adequate aeration and retention, thus ensuring the availability of nutrients and water. . This finding is in contrary to the low silt percentage (20.5%) and clay percentage (27%) obtained from this study. Cassava tolerates a wide pH range but performs best in moderately acidic soils. Research by FAO (1997) showed that, optimal yields of cassava are gotten at a pH (water) range of 4.5-6.5. This supports the findings of this research with similar soil pH (water) rage of 5.1-6.6. Also, the PH range (pH water plus pH KCl) from 4.0 to 6.6 indicated that, the soils were slightly acidic. This slightly acidic pH could also be associated with higher levels of fungal infections, particularly from pathogens like Fusarium and Colletotrichum. This finding is consistent with previous studies that report that, many soil borne fungi thrive in acidic conditions, thereby increasing disease prevalence (Santos et al., 2020; Nwankwo and Okeke, 2021). This is in line with the work of Adeniyi et al. (2011) concerning the changes in soil properties related tocassava production in Nigeria. This condition of the soil can be linked to the significant rainfall, exceeding 3500 mm per year, which removes basic cations from the soils in this area. . Also, the high levels of soil organic matter from this study confirmed the study of Ezui et al. (2016) who reported that, soil organic matter content significantly influences cassava productivity where optimal organic matter content range from 2-3%, contributes to improved soil structure and nutrient availability. The low nitrogen percentage (ranged from 0.028-0.616) was found insufficient to sustain intensive cassava production as the nitrogen levels were below the standard values of 30.2-53.2 % (Adeniyi et al., 2011). The low nitrogen percentage could be seen as the reason for disease attack on cassava due to poor feeding with respect to research by Fernandes et al. (2023) who reported that, cassava requires moderate nitrogen levels (20-40kg N/ha) for optimal growth, though excess nitrogen levels promote vegetative growth at the expense of root development. These levels of nitrogen could be attributed to rapid microbial activity and leaching of nitrates from the soil which, consequently, affects fungal communities and host microbe interactions (García-Jurado et al., 2011). Nutrient levels, particularly nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K), had no significant influence on fungal disease incidence and severity. This finding was in contrary to that of Hoffman and Smith (2019) who stated that, soils with higher nutrient content generally supported healthier plants, which exhibited lower disease severity. Also, well-nourished plants can better withstand pathogen attacks due to enhanced metabolic and defensive responses (Hoffman and Smith, 2019). Conversely, nutrient deficient soils were linked to increased disease severity, supporting the hypothesis that nutritional stress can predispose plants to infections. Organic matter content didn’t have any significant influence on fungal disease intensity. This contradicts the findings of Zhao et al. (2022), where higher organic matter levels were correlated with reduced disease incidence, likely due to improved soil structure, moisture retention, and microbial diversity (Zhao et al., 2022).

CONCLUSION AND APPLICATION OF RESULTS

Disease incidence in Bambili (0.66) was higher than that in Nkwen (0.50). On average, the severity of cassava disease in Bamenda according to disease severity scale is 2.55 (aprox.3) which represents less severe disease symptoms. These symptoms were more severe in Bambili (2.7) than in Nkwen (2.4). The soil physical properties were the same throughout the research farms while there were variations in the chemical properties of soils assessed. There was a positive correlation for soil chemical properties and disease intensity. The correlation coefficient between pH KCl and disease severity was 0.497, with a significance level of 0.026, indicating a positive correlation at P=0.05 and a positive correlation between disease incidence and severity, with a coefficient of 0.642 at a p=0.001. The other soil parameters didn’t show significant correlation with disease intensity. Therefore, the findings of the study has provided scientific insights that will guide sustainable disease control practices and improve cassava yield through a better understanding of the interaction between fungal pathogens and soil physicochemical properties.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors acknowledge the British Society for Plant Pathology (BSPP) for their financial support towards the realization of this work. We are grateful to the University of Bamenda, Bamenda University of Science and Technology, and the University of Dschang, Cameroon for providing material resources and all the laboratory assistants who assisted in the realization of this project.

Conflict of interests: The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Abera D, Kefyalew A., 2017. Characterization of physicochemical properties of soils as influenced by different land uses in Bedele area in Ilubabor Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia. Journal of Natural Sciences Research, 7(5):1–10.

Abiala MA, Odebode AC, Hsu SF., 2015. Fungal diversity and mycotoxin contamination of cassava root rot and control strategies. Journal of Agricultural Science, 7(5):83–92.

Acho CC. (1998). Human interphase and environmental instability: Addressing the environmental problems of rapid urban growth. Environment and Urbanization, 10(2), 415–422.

Adelekan BA., 2010. Investigation of ethanol productivity of cassava crop as a sustainable source of biofuel in tropical countries. African Journal of Biotechnology, 9(35):5643–5650.

Adeniyi AA, Adebayo AA, Ojo JA., 2011. Variation in soil properties on cassava production in the coastal area of Southern Cross River State, Nigeria. Journal of Geography and Geology, 3(1):94–104.

AGRISTAT, 2009. Bulletin No. 16. Ministère de l’Agriculture et du Développement Rural (MINADER), Cameroon.

Asaah A, Tanyileke G, Hell JV., 2013. Hydrochemistry of shallow groundwater and surface water in the Ndop Plain, Northwest Cameroon. African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 7(6):518–530.

Ayonghe SN., 2001. A quantitative evaluation of global warming and precipitation in Cameroon from 1930 to 1995 and projections to 2060: Effects on environment and water resources. Reading in Geography, 14:142–155.

Bailey KL., Lazarovits, G. 2003. Soil microbial diversity and soil-borne disease suppression. Advances in Applied Microbiology, 54, 1–27.

Berhanu K., 2017. Isolation, identification, and characterization of some fungal infectious agents of cassava in South West Ethiopia. Advances in Life Science and Technology, 54:2224–7181.

Boukhers I, Boudard F, Morel S, Servent A, Portet K, Guzman C, Vitou M, Kongolo J, Michel A, Poucheret P., 2022. Nutrition, healthcare benefits and phytochemical properties of cassava (Manihot esculenta) leaves sourced from three countries (Reunion, Guinea, and Costa Rica). Foods, 11(14):2027.

Du S, Trivedi P, Wei Z, Feng J, Hu H-W, Bi L, Huang Q, Liu Y.-R., 2022. The proportion of soil‑borne fungal pathogens increases with elevated organic carbon in agricultural soils. mSystems, 7(2), e0133721.

Ezedinma CI, Sanni L, Okechukwu R, Ogbe F., 2014. Environmental influence on cassava diseases and yield in Nigeria. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 9(14):1100–1106.

Ezui KS, Franke AC, Mando A, Ahiabor BD K, Tetteh FM, Sogbedji J, Giller KE., 2016. Fertiliser requirements for balanced nutrition of cassava across eight locations in West Africa. Field Crops Research, 185:69–78.

Fernandes AM, da Silva JA, Eburneo JAM, Leonel M, Garreto FGdS, Nunes JGdS., 2023. Growth and nitrogen uptake by potato and cassava crops can be improved by Azospirillum brasilense inoculation and nitrogen fertilization. Horticulturae, 9(3):301.

Fokunang CN, Dixon AGO, Ikotun T, Tembe EA, Akem CN, Asiedu R., 2001. Anthracnose: An economic disease of cassava in Africa. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences, 4(7):920–925.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations., 1997. The impact of cassava production on the environment. Rome: FAO.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations., 2021. Cassava – An emerging industrial crop: Statistical compendium for 2021. FAO.

García-Jurado I, Torrent J, Barrón V, Corpas A, Quesada-Moraga E., 2011. Soil properties affect the availability, movement, and virulence of entomopathogenic fungi conidia against puparia of Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae). Biological Control, 58(3):277–285.

Gountie DM, Njonfang E, Nono A, Kamgang P, Zangmo TG, Kagou DA, Nkouathio DG., 2012. Dynamic and evolution of the Mounts Bamboutos and Bamenda calderas by study of ignimbritic deposits (West Cameroon, Cameroon Line). Syllabus Review, 3(1):11–23.

Hillocks RJ, Thresh JM., 2002. Cassava: Biology, production and utilization. CABI Publishing.

Hoffman MT, Smith JA., 2019. Nutritional status and its impact on plant health: A review. Plant Pathology Journal, 35(3):123–130.

ISRIC., 2002. Procedures for soil analysis /LP. van Reeuwijk (ed.) AJ Wageningen. International Soil Reference and Information Centre. (Technical paper/ International Soil Reference and Information Centre. ISSN 0923-3792) no. 9. ISBN 90-6672-0441. PO BOX 353, 6700, The Netherlands. Sixth Edition.

Kakuhenzire R, Karamura DA., 2020. Climate change and its impact on the incidence of fungal diseases in cassava. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 15(5):123–130.

Keleko TD, Tadjou JM, Kamguia J, Tabod TC, Feumoe AN, Kenfack JV., 2013. Groundwater investigation using geoelectrical method: A case study of the western region of Cameroon. Journal of Water Resource Protection, 5(6):633–641.

Kinge RT, Zemenjuh LM, Bi EM, Ntsomboh-Ntsefong G, Annih GM, Bechem EET., 2023. Molecular phylogeny and pathogenicity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. elaeidis isolates from oil palm plantations in Cameroon. Journal of Plant Protection Research, 63(1):122–136.

Li Y, Zhang Y, Wang J., 2021. Different fertilizers applied alter fungal community structure in rhizospheric soil of cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) and increase crop yield. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12:749.

Machado AR, Pinho DB, Oliveira SAS, Pereira OL., 2014. New occurrences of Botryosphaeriaceae causing black root rot of cassava in Brazil. Tropical Plant Pathology, 39:464–470.

Mache JR, Signing P, Njoya A, Kunyukubundo F, Mbey JA, Njopwouo D, Fagel N., 2013. Smectite clay from the Sabga deposit (Cameroon): Mineralogical and physicochemical properties. Clay Minerals, 48:499–512.

Magdalena NMW, Mbega ER, Mabagala RB., 2012. An outbreak of anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloesporioides f. sp. manihotis in cassava in northwestern Tanzania. American Journal of Plant Science, 3:596–598.

Mahmood R, Bashir U., 2011. Relationship between soil physicochemical characteristics and soil-borne diseases. Mycopath (2011) 9(2): 87-93.

Mengel K, Kirkby EA., 1987. Principles of plant nutrition. 4th ed. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Meyo ESM, Dapeng L., 2012. Cassava sector development in Cameroon: Production and marketing factors affecting price. Agricultural Sciences, 3(5):651–657.

Morin S., 1988. Les dissymétries fondamentales des Hautes Terres de l’Ouest-Cameroun et leurs conséquences sur l’occupation humaine : Exemple des Monts Bamboutos. In L’homme et la montagne tropicale (pp. 49–51). Sépanrit Bordeaux.

Mwangi M, Bandyopadhyay R, Nolte C., 2004. The status of cassava mosaic disease, bacterial blight, and anthracnose as constraints to cassava production in the Pouma region of South Cameroon. In Proceedings of the 9th Triennial Symposium of the International Society for Tropical Root Crops – Africa Branch.

Nakarin S, Surapong K, Jaturong K, Ratchadawan C, Piyawan S, Saisamorn L., 2022. Morphology characterization, molecular identification, and pathogenicity of fungal pathogen causing Kaffir lime leaf blight in northern Thailand. Plants, 11(2):273.

Naylor RL, Falcon WP, Goodman RM, Jahn MM, Sengooba T, Tefera H, Nelson RJ., 2020. Biotechnology in the developing world: Threats and opportunities for the 21st century. Food Policy, 55:1–13.

Nelson DW, Sommers LE., 1982. Total carbon, organic carbon and organic matter. In: Page AL, editor. Methods of soil analysis: Part 2. Chemical and microbiological properties. ASA Monograph No. 9. American Society of Agronomy; Soil Science Society of America: 539–579.

Nwankwo N, Okeke J., 2021. Epidemiology of fungal diseases affecting cassava in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Botany, 34(3):45–58.

Nyaka NAIC, Kammegne DP, Ntsomboh NG, Mbenoun M, Zok S, Fontem D., 2015. Isolation and identification of some pathogenic fungi associated with cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) root rot disease in Cameroon. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 10(50):4538–4542.

Nyerhovwo JO, Okwu DE, Okwu AC., 2021. Products and by-products from cassava. In: Advances in Cassava Trait Improvement and Processing Technologies for Food and Feed. Kariuki SM, Muiruri AAF, editors. IntechOpen.

Nzenti JP, Abaga B, Suh EC, Nzolang C., 2010. Petrogenesis of peraluminous magmas from the Akum–Bamenda massifs, Pan-African fold belt. International Geology Review, 53(10):1121–1149.

Ogunsola AO, Ayansina ADV., 2019. Molecular identification and characterization of fungi associated with cassava diseases in Nigeria. International Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 4(1):19–26.

Ogweno JO, Karanja J., 2018. Fungal pathogens of cassava: A review of their impact on crop yield. African Journal of Microbiology Research, 12(4):78–85.

Okereke VC, Nwachukwu EO, Ogbulie JN., 2017. Identification and pathogenicity of fungi associated with cassava root rot. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology, 19(1):141–146.

Olsen SR, Cole CV, Watanabe WS, Dean LA., 1954. Estimation of available phosphorus in soil by extraction with sodium bicarbonate (USDA Circular 939). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC.

Onyeka TJ, Ekpo EJA, Dixon AGO., 2018. Epidemiology of cassava root rot disease and implications for its management. Plant Pathology Journal, 17(3):123–130.

Otaiku AA, Mmom PC, Ano AO., 2019. Biofertilizer impacts on cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) cultivation: Improved soil health and quality, Igbariam, Nigeria. Iris Publishers.

Oyewole OB, Odunfa SA., 1988. Microbiological studies on cassava fermentation for “lafun” production. Food Microbiology, 5:125–133.

Pitt JI, Hocking AD., 2009. Fungi and food spoilage. Springer.

Prochnik S, Pradeep RM, Dow A, Brian AD, Pablo DR, Chinnappa DK, Roche MM, Fautso RZ., 2012. The cassava genome: Current progress, future directions. Tropical Plant Biology, 5(1):88–94.

Sanginga N., 2015. Root and tuber crops (cassava, yam, potato and sweet potato). In: An action plan for African agricultural transformation conference (pp. 21–23). Dakar, Senegal.

Santos ECD, Pirovani CP, Correa SC, Micheli F, Gramacho KP., 2020. The pathogen Moniliophthora perniciosa promotes differential proteomic modulation of cacao genotypes with contrasting resistance to witches’ broom disease. BMC Plant Biology, 20:1.

Sayre R., 2011. The BioCassava Plus Program: Biofortification of cassava for sub-Saharan Africa. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 62:251–272.

Theberge RL., 1985. Common Africa pests and diseases of cassava, yam, sweet potato and cocoyam. IITA, p. 107.

Waller, J. M. and Jeger, M. J. (1998). Screening Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f.sp. manihotis isolates for virulence on cassava in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Plant Pathology, 47(3), 357–362.

Wokocha RC, Nneke NE, Umechuruba CI., 2010. Screening Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. manihotis isolates for virulence on cassava in Akwa Ibom State of Nigeria. Journal of Tropical Agriculture, Food, Environment and Extension, 9(1):56–63.

WUP., 2011. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs/Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2011 Revision, pp. 1-302.

Zhao L, Zhang T., 2022. Sustainable practices for enhancing crop resilience: A focus on soil microbiome. Sustainability in Agriculture, 8(2):112–124.